|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

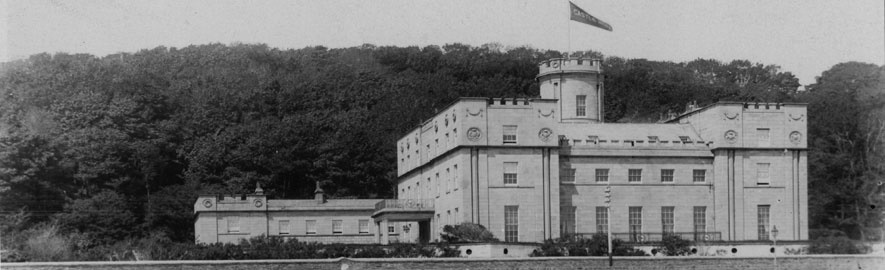

Castle Mona, home to the Manx, or Isle of Man, Casino, 1964

1961-1966

“When you bring in gamblers, you bring in trained law violators, and to expect them not to break the law is to expect the tides not to rise,” Wallace Turner wrote in Gambler’s Money.

The Manx Casino, also called the Isle of Man Casino, named for its locale, was a case in point.

A Dubious Proposition

The enterprise came about despite and after much opposition to the idea. The roughly 300 Methodist Manx “raised hell about a gambling joint on the island,” Turner wrote.

The Manx government itself wasn’t sold on it entirely, which led to heated debate. Even England hadn’t considered legalizing gambling yet and wouldn’t do so until 1962.

“Some politicians portrayed casino gambling as an act that could subvert the Isle of Man’s respectability, but also one that surrendered national sovereignty by making the Manx Treasury subservient to the taxation revenue procured from multinational gambling magnates,” Pete Hodson wrote in the 2018 article, “‘The Isle of Vice?'”

The Manx House of Keys legalized gambling with a 15-to-9 vote on the Pool Betting Act in 1961.

Two years later, in May 1963, the Manx Casino debuted, the first gambling house in the British Isles.

“Anxious politicians and members of the public were reassured that the casino would be subject to tight regulation, and that unruly behaviour would not be tolerated,” wrote Hodson.

Americans at the Helm

Initially, the gambling enterprise was sited in a temporary spot, inside Castle Mona, a hotel in the Douglas Promenade. Plans called for it to be moved later to a permanent location.

Casino Ltd., a group of Americans, held and operated the gambling concession. They included three Maryland businesspeople: William A. Albury and John D. Hickey, who headed it, and silent partner Helen Saul who provided most of the required upfront capital. Frank O’Neill, 49, was the casino director; Las Vegan William Paris, 39, was the deputy director; Raymond Gavilan, 45, supervisor; and Arthur P. Anderson (Hickey’s nephew), 23, cashier. James D. Gilson was another employee.

The syndicate was to pay the Manx government €5,000 pounds a year plus 15 percent of its profits.

Because half of the island’s economy relied on tourist spending at the time, the casino catered to the middle and lower classes.

“The betting was to be on the ‘Woolworth principle,’ of small stakes and large turnover of bettors. No French phrases were used,” Turner wrote. “[Patrons] even were offered lessons in roulette, chemin de fer, blackjack and craps.”

Prediction Comes True

After employee Gilson tipped off the police, they raided the casino in December and investigated the finances. O’Neill, Paris, Gavilan and Anderson were arrested and charged with conspiring to steal money from the Manx Casino since it opened and receiving stolen money, “‘thereby defrauding both the casino company and the government,” Manx Attorney General David Lay said, as quoted by Turner. The quartet was jailed and stripped of their work permits and passports.

Six months later, in late June, the former casino employees’ trial began.

Lay, the prosecutor, argued the four employees had engaged in fiddles, or types of swindling, including fudging the amounts on cash-out slips, I.O.U.s and checks, to allocate money to be skimmed, which then had been. From the skim, the wages of the four men had been paid. In carrying out these irregularities, Lay said, the defendants had defrauded the casino company and the government.

Palace Hotel & Casino, Douglas, Isle of Man

Defense Barrister Rose Heilbron countered that the defendants simply had been following orders of their bosses Albury and Hickey in regards to the skimming and their pay. As such, the company had known all along the funds were being stolen.

Rather than the four employees, Heilbron purported, Casino Ltd.’s two executives, who since had fled the Isle of Man, should’ve been the ones on trial. One had to wonder why they weren’t, she noted.

She charged that Albury and Hickey “had drawn cheque after cheque for unknown purposes. The fiddle had been to give the two tax-free living. The casino had provided the perfect front for all Albury’s activities” (Liverpool Echo and Evening Express, July 1, 1964).

Ultimately, the jury found all four men guilty of conspiring to steal. The judge sentenced them to spend six months in prison, pay a fine — O’Neill and Paris, €300, Gavilan €150 and Anderson €75 — and possibly be deported.

(A swindle by a different set of Americans would take place in England in 1969.)

The Next Phase

In 1964, the Palace Coliseum, in the Douglas Promenade, was demolished, and in its place a new building was constructed for the Manx Casino and a hotel.

The gambling facility, which Scottish actor Sir Sean Connery ushered in, opened in May 1966 under a different name, Palace Hotel & Casino.

“I wish the people in London could see the Casino,” he said. “There is nothing like it there!”

———————–