|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1939

With the recent discoveries of dead bodies there, Lake Mead in Southern Nevada has been in the news.

The 1.5 million acres encompassing this water body and its environs have been a designated national recreation area since 1964, but a portion of them almost had become a Nevada state park three decades earlier.

The federal government quashed the effort to establish such an entity due to gambling, in part.

Piece of the Pie

Nevada Senator Key D. Pittman introduced a bill to the U.S. Congress in early 1939 that would carve out about 10,000 acres (or 12 square miles out of 2,600) of publicly owned lands on the Boulder Dam National Recreation Area and authorize The Silver State to use them for a park.*

The recreation area, about 18 miles from Las Vegas, included the lake that Hoover Dam (previously called Boulder Dam) created, Lake Mead, named after Elwood Mead, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation commissioner at the time.

The National Park Service had gained responsibility for Lake Mead and the surrounding land in October 1936. About 10 years later, the name was changed to the Lake Mead National Recreation Area. The attraction drew about 500,000 or more visitors each year.

All About Gambling

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes attacked Pittman’s state park idea, purporting that gambling and liquor interests were behind it. He argued that the 160 acres, allocated in the bill for the state park or “other public purposes,” likely would be used for saloons and gambling houses.

To support these claims, he alleged that, according to circulating rumors, gamblers being driven out of Los Angeles in a citywide cleanup intended to open shop in the Lake Mead area to capitalize on the numerous tourists visiting the lake and dam.

“I believe that the people of the United States want the integrity of their national park areas preserved,” Ickes said (Reno Evening Gazette, March 7, 1939).

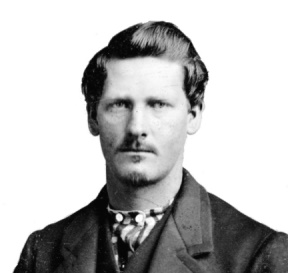

Guy McAfee

Ickes didn’t name anyone but was referring to Guy McAfee, according to Charles “C.D.” Baker, president of the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce. McAfee was a former Los Angeles Police Department officer and gambler who’d moved from the City of Angels to Las Vegas due to heat from law enforcement in the former in 1938. The next year he’d acquired and renamed the Pair O’ Dice Club, on Highway 91 between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, the 91 Club. Also, he’d debuted the Frontier Club in downtown Sin City. Baker refuted Ickes’ claims about gamblers, emphasizing McAfee had nothing to do with the proposed state park.

“That is a cooked-up charge to cloud the issues,” Baker said, referring specifically to Ickes’ assertion that Nevada wanted the state park so gambling establishments could be operated and liquor sold at it (Reno Evening Gazette, March 8, 1939).

Baker conceded, however, that Las Vegas wanted the state park so that Nevada, instead of the federal government, could control and benefit economically from the non-gambling/non-alcohol concessions there.

Ickes contended, too, that were Pittman’s bill to become law, it would set an unwise precedent and encourage other states to demand parcels of national parks.

Attempts to Appease

In response to Ickes’ opposition, Pittman expressed his belief that “western lands are rapidly becoming a barony, of the dictator at the head of the Department of the Interior,” but the senator also took steps to resolve the concerns.

He amended his bill. The new verbiage indicated Nevada would forfeit the federal grant for a state park if it “fails to put into effect and practice in said area laws, rules and regulations put into effect and practiced by the Department of the Interior within the Boulder canyon reclamation area relative to gambling, sale of intoxicating liquors, water pollution or sanitation” (Reno Evening Gazette, March 7, 1939).

Pittman also encouraged the Nevada State Park Commission (NSPC) to ban gambling and liquor sales in Nevada parks, which the agency did.

State Support

While Pittman worked in Washington, D.C. on the state park idea, Nevada legislators did so on the home front. They passed Senate Bill (SB) 133, which authorized the governor to accept a grant of land for a state park at Boulder Dam. They also approved SB 132, which authorized the NSPC to prohibit gaming and alcohol sales in the potential state park at Lake Mead.

The Finale

The fate of Pittman’s bill became known in August, when U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt vetoed it. His reasons for doing so echoed Ickes’ voiced criticisms of the Nevada state park prospect except those related to gambling and liquor.

“I firmly believe the Boulder Dam/Lake Mead region in its entirety should continue to be administered uniformly by federal government in the interest of the nation as a whole,” Roosevelt said (Nevada State Journal, Aug. 13, 1939). He added that the area warranted consideration as a national park or monument site. (About 25 years later, the federal government officially made it a national recreation area.)

Angry at the decision by Roosevelt, specifically that he’d based it on Ickes’ input, as reported by the press, Pittman issued a statement. In it, he suggested the U.S. president might lose support in western states due to his public land policy.

——————————-

* At the time, Nevada had four state parks, including the Valley of Fire, all of which the legislature had established in 1935.

Photo by Tony Webster