|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1864-1983

1864-1983

While being plied with endless, free whisky highballs,* Hamilton Buck played roulette for hours at the Texas gambling-saloon** in Goldfield, Nevada. Then, in 1908, the northwestern mining town was nearing the end of its heyday (1904-1908) that had made it the state’s largest metropolis.

With Charles Green, a brother of one of the establishment’s proprietors comprising J.E. Burke & Co., operating the wheel, Buck had varied luck for a while. Ultimately, though, he found himself $1,000 (more than $26,000 today) in the hole.

He gave Green a $500 certificate of deposit (COD) he’d gotten from the local John S. Cook & Co. bank, and Green exchanged it for gold coins. With those, Buck continued to gamble at roulette. At first he won about $700 to $800 but eventually lost most or all of the $500. An intoxicated Buck left the establishment.

The next morning, he instructed the bank to cancel payment on the COD because Burke & Co. weren’t entitled to it legally. In response, Burke & Co. sued Buck and won; Cook & Co. had to make good on the COD. Dissatisfied with the outcome, Buck appealed, and J.E. Burke & Co. vs. Hamilton Buck went to the state’s high court.

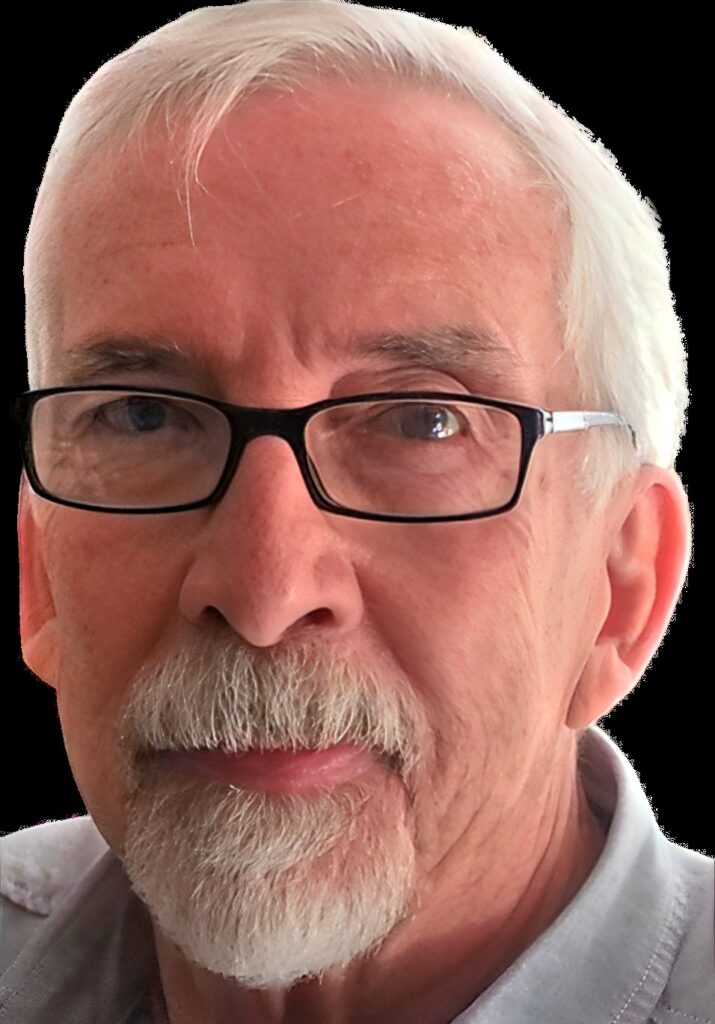

James G. Sweeney

Significant Ruling

In January 1909, the Nevada Supreme Court reversed the Esmeralda County district court’s ruling and mandated that the saloon reimburse Buck the $500. The basis for the decision, Justice James G. Sweeney wrote in the opinion, was the Statute of 9 Anne, part of the revised English common law that became the basis of Nevada law upon statehood in 1864.

Based on the belief that gambling was against the public’s interest, the statute read: “… all notes, bills, bonds … given … by any person or persons whatsoever, where the hole or any part of the consideration … shall be for any money or other valuable thing whatsoever, won by gaming, … shall be utterly void, frustrate, and of none effect, to all intents and purposes, whatsoever, etc.“

Sweeney clarified that money won at a public gaming table is not recoverable by action in Nevada. He also noted that the statute stands regardless of whether gambling is considered by state law to be legal or illegal. (Later that year, the Nevada Legislature abolished gambling.)

Burke v. Buck was one of the earliest Silver State cases challenging the statute.

The Flip Side, Player v. Casino

In July 1958, the Nevada Supreme Court weighed in on the reverse, whether players may sue gambling clubs for alleged unpaid winnings. This came about through the lawsuit of Jack Weisbrod against the Fremont in Las Vegas. He claimed the casino refused to pay him the $12,500 ($111,000 today) he believed he’d won from playing keno.

The district judge rejected Weisbrod’s suit, and the high court jurists affirmed the ruling. They wrote that “if money won at gambling is not recoverable through resort to the courts, it is not because of who has won it but because of the nature of the transaction itself.”

They noted, too, that players have recourse through the state’s gambling regulators who will intervene on their behalf, if warranted.

A Long Stretch

The Statute of 9 Anne endured in Nevada for 119 years despite several legal tests of it and attempts to have it reversed.

Casino owners in the state again lobbied for the latter in 1982 because of their “staggering money losses,” about $117 million ($311 billion today) that year for instance, and because their Atlantic City, New Jersey competitors could collect on markers, the Reno Gazette-Journal reported (Dec. 17, 1982).

When the legislature was in session the following year, it passed Senate Bill 335 allowing gambling establishments to pursue in the courts the monies owed to them.

———————————

* A whisky highball at the Texas consisted of Scotch whisky and mineral water.

** The Texas burned down in 1914.

Photo from freeimages.com: “Money Series 6” by mokra