|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1835

During Andrew Jackson’s U.S. presidency, anti-gambling sentiment began sweeping the Southern states. By 1835, it had hit Louisiana and was making its way up the Mississippi River. The fever peaked mid-year in Vicksburg, Mississippi when a band of vigilantes committed a criminal act that shocked the world.

Generally, the steps taken to eradicate gambling in a region included passing laws prohibiting the activity, ordering gamblers (operators and professional cheaters) to leave the jurisdiction and raiding and shutting down illegal operations. What happened in Vicksburg, however, was unprecedented and radical.

The Last Straw

Dissent toward the gamblers in the city burgeoned over a couple of days, starting on July 4 at a party held by the corps of Vicksburg Volunteers and attended by numerous residents. When, at the shindig, an officer attempted to quiet everyone for a toast, a gambler named Francis Cabler allegedly insulted him and then hit a guest. Cabler was shown the door.

After the festivities ended, many of these militia members as well as locals went to the city’s public square. Cabler showed up, too, and made a beeline for the group. Before he reached it, however, two volunteers arrested him and found a loaded gun, knife and dagger on his person.

The mob tied him to a tree, tarred and feathered him and ordered him to leave Vicksburg within 48 hours.

Get Out or Else

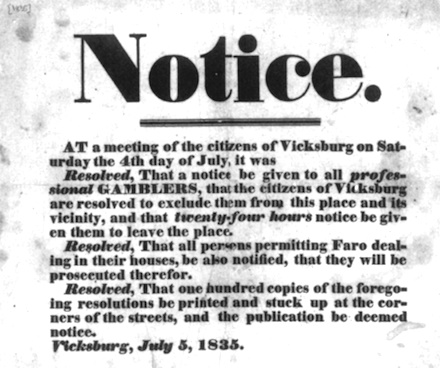

That night, numerous Vicksburg residents met in the courthouse, formed an ad hoc anti-gambling committee and passed the following resolutions, as noted in a Vicksburg dispatch published in numerous newspapers, including The Watchman:

- “That a notice be given all professional gamblers, that the citizens of Vicksburg are resolved to exclude them from this place and its vicinity; and that 24 hours’ notice be given them to leave the place.”

- “That all persons permitting faro dealing in their houses, be also notified that they will be prosecuted therefor [sic].”

- “That 100 copies of the foregoing resolutions be printed and stuck up at the corners of the streets — and that this publication be deemed notice.”

The next morning, Sunday, July 5, the notices were posted throughout the city.

Crescendo of Violence

Immediately after the deadline passed, on the 6th, the militia, followed by several hundred citizens, marched to and stormed the “kangaroos,”* the known and suspected gambling houses in the waterfront district. In their frenzy, this vengeful faction destroyed any gambling equipment it came upon, leaving pieces of faro tables and roulette wheels in its wake.

The multitude sought out the coffeehouse owned by Alfred North, “one of the most profligate of the gang,” the Vicksburg report described. Acting on the rumor that armed gamblers were hiding inside, the mob surrounded the building and burst open the back door, which revealed only darkness.

The occupants fired their guns, instantly killing one of the pack’s leaders, reportedly a well-respected community member.

“This unexpected reception aroused the citizens to madness and desperation,” wrote the Natchez Courier (July 13, 1835).

The vigilantes shot back, and a bloody riot ensued. Outnumbering and overpowering the gamblers, the disgruntled mob extracted the four men inside, one of whom had been hit by a bullet. North wasn’t among them, but someone apprehended him nearby.

Before a mass of looky-loo townspeople, the alleged gamblers were hanged. Those executed were North, Hullums, Dutch Bill, Smith and McCall (full names weren’t published).

“All sympathy for the wretches was completely merged in detestation and horror of their crime,” the Vicksburg dispatch noted, referring to the gamblers.

Next, the entire procession collected, piled and burned all of the wooden gambling equipment littering the streets.

The following day, July 7, the dangling corpses were cut down from the gallows and buried in a ditch.

In the Minority

The dispatch from Vicksburg indicated that its citizens wholly supported the lynchings and those who carried them out. The report read:

“Our city has for some days past been the theatre of the most novel and startling scene that we have ever witnessed. While we regret that the necessity for such scenes should have existed, we are proud of the public spirit and indignation against offenders displayed by the citizens, and congratulate them on having at length banished a class of individuals, whose shameless vices and daring outrages have long poisoned the springs of morality, and interrupted the relations of society.”

On the other hand, much of the rest of the U.S. and the world considered the lynchings vile. One such opinion was published in The Watchman (Aug. 8, 1935). It read, “It seems to us that the proceedings of the people of Vicksburg cannot be sanctioned by any well regulated mind. They are subversive of every principle of law and the good order of society, and ought to be discountenanced with horror by every good and just man.”

Exodus to More Tolerable Locales

After the Vicksburg murders, other towns along the Mississippi River exiled the gamblers from their communities.

The “proceedings at Vicksburg have kindled a spirit throughout the lower country which is breaking forth at every point, and obliging the blackleg fraternity to make their escape with all haste,” reported Niles’ Weekly Register (Aug. 8, 1835).

Due to these expulsions, the gamblers moved en masse to the West Coast.

—————————————

* The people of Vicksburg referred to the local gambling houses as “kangaroos” because one of the former casinos, which had burned down the year before, was called the Kangaroo Saloon.