|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

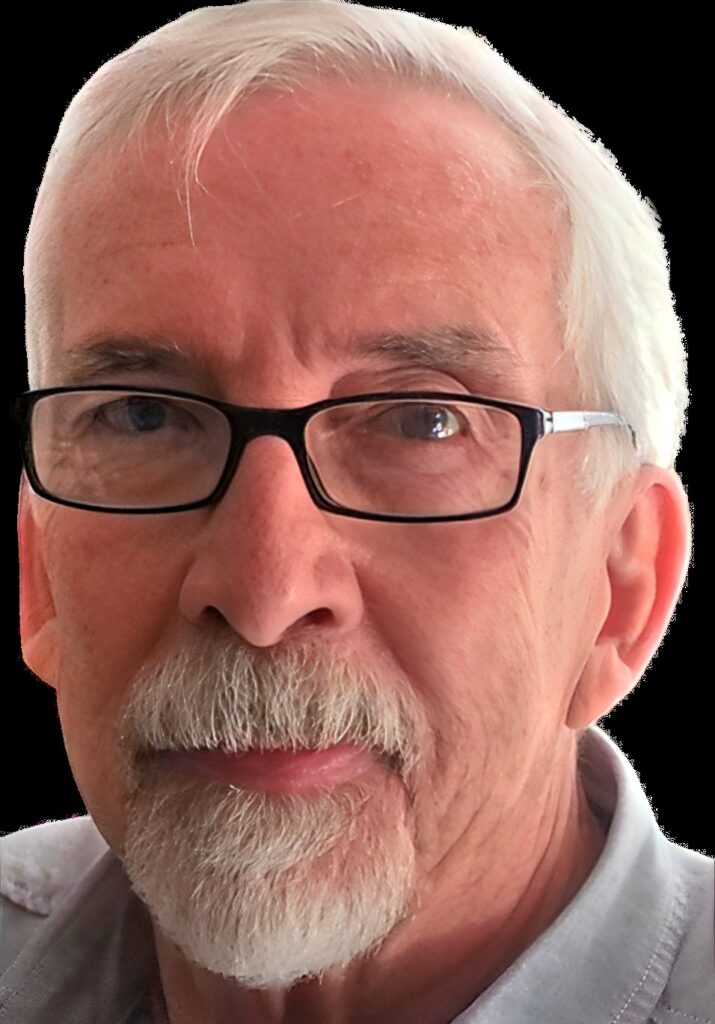

Earl Warren (front center) and the rest of the U.S. Supreme Court justices, 1967

1952-1968

Soon after two new federal taxes — the tax on wagers and the wagering occupational tax — went into effect in late 1951, problems with them arose. (See Part I for a description of and impetus behind the taxes.)

First Complication to Arise

The constitutionality of the occupational tax was called into question. In May 1952 U.S. District Court Judge George A. Welsh flat out declared it federal legislators’ unconstitutional infringement on states’ power and described it as “a police measure enacted by Congress under the guise of a tax bill” (Reno Evening Gazette, May 6, 1952). This ruling came during the trial of a Philadelphia gambler charged with failure to buy the gambling tax stamp.

An editorial in Florida’s Tampa Times pointed out the gambling stamp tax was “contradictory” and “hypocritical” (March 3, 1953).

“It is a case of the federal government on one hand sanctioning gambling, while state and local law enforcement officers are expected to stamp out gambling,” it read. “Winking at gambling because it has become a federal tax revenue producer would be outright hypocritical and against the wishes of the majority of Americans.”

Other critics argued the tax violated wager-takers’ Fifth Amendment right to protection from self-incrimination. On one hand, requiring them to register forced them to provide information that could implicate them in breaking their state’s state anti-gambling law, were that in fact the case, and in doing so, invite prosecution. Many newspapers, including The Sacramento Bee and The Indianapolis News, published the names of stamp purchasers.

On the other hand, if the wager-takers ignored the federal law, to keep their underground gambling operation secret, they risked federal prosecution for not buying the stamp and registering.

Not So Effective

A second issue was the taxes weren’t achieving the desired ends. A year in, they hadn’t significantly reduced gambling; at best, they’d slightly deterred it. They hadn’t forced gamblers out of business; instead, the operators had gone underground.

The taxes also failed to bring in anywhere near the level of revenue expected. Congress had predicted an influx of about $400 million in the first year, but the actual figure was about $9 million, not even one-third of the predicted amount.

Whereas a flurry of stamp tax buying had occurred after the Revenue Act was passed, taking total sales to over 19,000, purchases dramatically fell off in 1952.

“The professional gamblers soon wised up and developed a ‘wait and see’ attitude,” reported The Tampa Times.

The reasons for the suboptimal results, according to Frank Lohn, chief of the Internal Revenue Bureau’s intelligence division, were that the bureau lacked sufficient staff to go after unpaid gambling taxes and that the constitutionality of the special tax remained undecided.

“Many gamblers believe the high court will overturn the law, and in the meantime they are not too afraid of violating it,” reported the United Press (Reno Evening Gazette, Nov. 1, 1952).

High Court Weighs In … Twice

That was not the case, however; the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the special tax, 6 to 3, in March 1953. About a year later, it ruled that purchasing a wagering stamp tax did not make the buyer immune from possible state prosecution, thus the self-incrimination problem persisted.

Fast forward 14 years to 1967. Significantly fewer gamblers nationwide were buying a tax stamp, 5,917 in that year, for example. About 2,000 gambling tax violation cases were advancing through the courts.

Then in January 1968, in another twist, the Supreme Court, in a 7-to-1 decision, ruled that the stamp tax law violated people’s Fifth Amendment right, but the justices didn’t declare it unconstitutional. Instead, they essentially gave wage-takers a way to avoid prosecution for noncompliance: claim self-incrimination.

The sole dissenter, Chief Justice Earl Warren, said the decision made the law unenforceable and unconstitutional. Justice and treasury department officials predicted it would hamper crimefighting at the federal, state and local levels and jeopardize current prosecutions.

Fix For The Problem

In 1974, Congress passed Public Law 93-499 to replace the two wagering taxes mandated in 1951. The new statute required certain gamblers to buy a $500 (about $2,800 today) wagering tax stamp annually and pay 2 percent on all bets they take. December 1, 1974 was the effective date, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms was tasked with enforcement.

This law avoided the Fifth Amendment issues inherent in the previous one. It did so by prohibiting the federal government from divulging, to any law enforcement agency, private group or citizen, the information gamblers gave, as required, about themselves, their partners, employees and customers.

Types of gambling exempt from the new law were casino betting, state-licensed parimutuel wagering, state lotteries and coin-operated machines on which a stamp tax was charged.

As with the prior wagering taxes, the purpose of Public Law 93-499 was to “increase federal revenues and curtail an important source for financing criminal activities” — certain types of gambling, reported The Sun-Telegram (Jan. 19, 1975).