|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

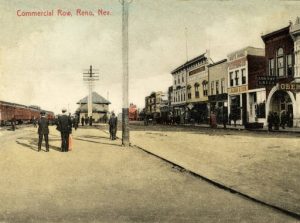

Commercial Row, Reno, Nevada. early 1900s

1924-1932

The story of the estate of a long-ago Nevada gambler after his passing is strange and unfortunate.

John Quinn was a man who’d lost and made large fortunes in gambling and mining stock deals throughout The Silver State and other parts of the West.

He’d opened the first saloon-gambling house in the mining town of Taylor in the 1870s, for one. He’d been a partner in Nolan, May & Quinn, “which conducted the most liberally patronized gambling institution that ever graced Reno’s palmiest days” — the Palace casino at Commercial Row and Center Street between 1906 and the year the state had outlawed gambling, 1910 (Nevada State Journal, June 8, 1924).

“The Palace was one of the last of the celebrated western gambling halls, elaborately fitted and equipped with gorgeous chandeliers, mirrors, a mahogany bar, and an excellent assortment of money makers in the form of roulette wheels, faro banks, craps and card tables,” recalled the Nevada State Journal (Dec. 2, 1926).

Question of Heirs

1924

John died of pneumonia at 85 years old in June in Needles, California, where he’d lived the previous 14 years. He left behind substantial assets —about $100,000 worth in California ($1.4 million today) and $33,000 worth in Nevada ($470,500 today).

John wasn’t thought to have any relatives, but a San Francisco-based attorney, Charles L. McEnerney, through an heir-hunting firm, found at least a son and five grandchildren residing in The Golden State. Although the gambler always had represented himself as unmarried, he’d abandoned his wife and children in Illinois decades earlier. In October of that year, McEnerney was appointed the administrator of John’s estate.

Suspicious Behaviors

1926

McEnerney failed to appear at a subsequent routine hearing concerning the California estate. Soon after, it was discovered that all but $437 of the $100,000 had disappeared. All parties involved suspected the administrator had misappropriated it.

An investigation revealed that McEnerney, in his past, had served time at San Quentin State Prison for burglary and previously in the 1890s, had pocketed $600 from the Vallejo post office where he’d worked.

When faced with fraud charges over the missing Quinn money, McEnerney pleaded insanity and was hospitalized at Agnews State Mental Hospital in California for an indefinite period. One of John’s grandsons, Eugene Quinn, was granted control of John’s estate.

A probe of John’s Nevada holdings began as well after Eugene learned 20,000 shares of the Palace property had been sold but no transaction record filed. That query brought to light that the $33,000 also had been depleted, by about $23,000. The theory was McEnerney had stolen those monies, too.

Taking Responsibility?

1928

In March 1928, McEnerney was released from the institution and immediately arrested on grand theft charges in California.

1930

In late spring, the since-disbarred attorney asked the court to return him to sane status; it was granted. Five months later, his trial for embezzlement of John’s California estate began in the City by the Bay.

He was convicted only of stealing $8,000 from the Quinn estate and sentenced to 1 to 10 years at Folsom State Prison for grand theft.

Recouping Where Possible

1932

After several legal maneuvers, Eugene, with the court’s approval, sued the United States Fidelity Company for $23,000 misappropriated from John’s Nevada estate because the insurer had provided $35,000 of surety for McEnerney during his stint as its administrator.

The bond company argued the court-appointed attorney-investigator’s accounting was faulty and the Nevada court had lacked jurisdiction in ordering the financial reconstruction.

Eventually, the two parties agreed to a compromise. United States Fidelity would pay $12,500 ($222,500 today) — roughly the difference between the bond figure and the stolen amount — to John’s estate.

With that amount being all, the Quinn heirs received only 10 percent of John’s wealth; the other 90 percent was gone, with no explanation.

Photo from the University of Nevada, Reno Library’s Special Collections