|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1951

Gambling is the lifeblood of organized crime.

This was U.S. Senator Estes Kefauver’s conclusion after the Special Committee on Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, which he headed, concluded its investigation.

The Kefauver Committee’s work, in part, involved conducting hearings in 14 U.S. cities, during which they grilled (sometimes, unsuccessfully) about 600 witnesses, including big-time Mobsters, some of their associates and officials knowledgeable about Mob activity. The 15-month query shone a spotlight on gambling taking place at the time and for years before, most of it illegal, prohibited by law in most states.

The hearings were televised, and Americans tuned in, rapt. The broadcasts opened their eyes to the who, what, where, when and how of gambling and other organized crime happening all around them. By March 1951, 72 percent of U.S. residents were familiar with the Kefauver committee and what it was doing.

Crackdown on Some Gamblers

As a result of the Senate committee’s findings, Kefauver recommended the federal government impose a 10 percent tax on all gambling. At the same time, U.S. residents, facing a likely federal personal income tax increase, expressed dissatisfaction at gambling operators (gamblers) paying little or no taxes on the loads of cash they made.

These two factors in large part pressured Congress to act, and it did in 1951 but not to the extent Kefauver had suggested. It imposed two taxes* on a subset of gamblers, individuals who received bets from people — bookmakers, numbers writers, and punch board and lottery operators.

The goal was to force these people to pay heavy taxes or go out of business, and in doing so, shrink the gambling industry nationwide and generate a good chunk of revenue for the U.S.

Trio of Mandates

One of the new federal levies, called the tax on wagers, was 10 percent of all gross receipts.

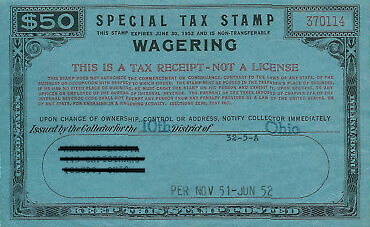

The other was an occupational tax, often referred to as the gambling stamp tax. It required wager takers to buy a special tax stamp every year by December 1 and display it in their place of business or, for those without such a location, on their person. The stamp cost $50 (about $525 today).

Anyone required to pay the special tax also had to register with the local Internal Revenue Bureau (IRB) collector and provide their name, home and business addresses and the name and home address of their partners, employees and clients. Once the bureau received the information, it provided a copy to local law enforcement officials and maintained its own public list of all gambling stamp purchasers.

These wagering-related taxes went into effect on November 1, 1951.

Failure to Comply

The penalty for not purchasing the $50 tax stamp was a fine of at least $1,000 ($10,300 today) but not higher than $5,000 ($51,500 today).

Gamblers who had a stamp but didn’t display it were fined, $50 for those who’d forgotten to do so and $100 for those who outright refused to do so.

Providing false information on the relevant forms was punishable by up to $10,000 in fines and five years of imprisonment.

Regarding the 10 percent tax on wagers, IRB Commissioner John B. Dunlap told the United Press that “cases of willful evasion or attempt to defeat the tax will be promptly referred to the department of justice with recommendation for criminal prosecution” (Nevada State Journal, Dec. 5, 1951).

Early Stamp Numbers

By the first deadline, December 1, 1951, a total of 7,706 gamblers had applied for the federal gambling tax stamp. The state of Washington submitted the most applications, at 1,412. Next was Montana, with 902. Nevada, where gambling was legal and wide open, accounted for only 33 applications.

It wasn’t long before problems with these latest federal taxes arose.

———————————–

Look for Part II next week.

* Congress enacted the two taxes on wage takers through the Revenue Act of 1951, which also temporarily raised federal individual income and federal corporate taxes.