|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

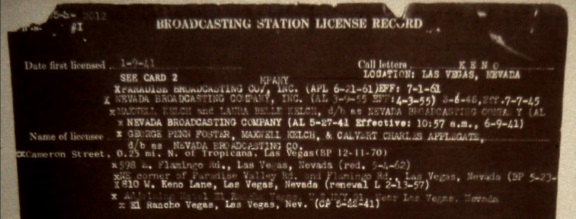

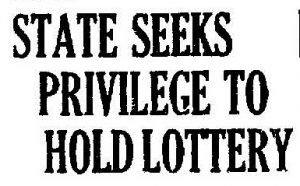

Headline, Nevada State Journal, January 26, 1939

1937-1939

A ticket would cost $1 (about $17 today). A drawing would be held at least every 90 days, maybe monthly if demand was great enough, on the last Saturday night of the month. It would alternate between all Nevada towns, starting with Reno, then Las Vegas.

This was the proposal for a Nevada lottery made by Senator William A. Marsh (D-Nye County) and Assemblyman Patrick Cline (D-Clark County) in 1937, at a time when the state constitution prohibited this game of chance but allowed numerous others. The first such attempt to institute this gambling type, which had failed, had been in 1888 when “state finances were in a parlous* condition” (Reno Evening Gazette, Nov. 22, 1928).

“We are living in a liberal state where we do not presume to be our brother’s keeper, and that is as it should be. We believe that if anyone wants to gamble a dollar on a lottery ticket and stand a chance of winning from $150,000 ($2.5 million today) down to $1,000 (about $17,000 today), he should be able to buy that ticket from the state of Nevada,” Marsh and Cline said in a joint statement.

They added that Americans spend $250 million ($4.2 billion today) each year on lottery/ sweepstakes tickets, and that money was going to Ireland, Mexico and Canada rather than staying at home.

Big, Big Picture

The duo estimated with the new scheme that ultimately $1 million worth of Nevada tickets ($16.8 million today) would be purchased per month, 90 percent of them by out-of-staters despite sales being limited to within The Silver State’s borders. After expenses, the net monthly profit would be $450,000 ($7.5 million today), which would be distributed as follows with the ultimate goal of eliminating property taxes:

• To reducing property taxes, $325,000 ($5.5 million today)

• To the state’s school fund, $50,000 ($838,000 today)

• To a pension plan for seniors, $50,000

• To building and maintaining a hospital for children with disabilities, $50,000

• To the University of Nevada, $25,000 ($419,000 today)

Winnings would be dispersed this way:

• First prize, $150,000 ($2.5 million today)

• Second prize, $75,000 ($1.3 million today)

• Third prize, $60,000 ($1 million today)

• Ten prizes, each $10,000 ($168,000 today)

• Ten prizes, each $5,000 ($83,000 today)

• Twenty-five prizes, each $1,000 ($17,000 today)

The proposal also included the establishment of a lottery commission comprised of three legislature-appointed, nonpartisan men who’d administer the game according to the law, answering to the state controller and treasurer only.

Opposing Views

Several individuals publicly criticized the idea and vowed to fight it. Here are their arguments:

• Slippery Slope: If petitions are circulated to legalize a state lottery by an amendment to the constitution, a similar move will be started against all forms of gambling, Rev. Brewster Adams of the Baptist Church said.

• Goes Too Far: “While this state is liberal, there is a limit to liberality and nothing destroys tolerance as much as abuse, which this proposal certainly is,” said Mrs. Clara Angell, president of the Reno chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (Nevada State Journal, Jan. 7, 1937).

• Negative Publicity: “It would be a sad reflection on the state of Nevada if we were not able to raise enough money to run the state,” said Robert M. Price, Reno attorney. “The government of Nevada is doing very well with the present taxes and it would be poor advertising to let other states think that we need to resort to gambling.”

• Morally Wrong: Gambling is the hardest vice to eliminate, said Reverend William Moll Case. “The proposal is foolish.”

Looking Good

The Assembly voted against the resolution to amend the constitution to permit operation of a state lottery. The Senate, however, did the opposite and then returned the bill to its counterpart for reconsideration. On its subsequent vote, the lower house passed it by a single aye.

This, however, was only the first step. To create a lottery, state lawmakers would have to pass the bill in the next legislative session (1939), and then Nevadans would have to vote to approve it.

Final Curtain

When 1939 rolled around, Cline no longer was in office, and Marsh had passed away the year before.

Again, the Nevada Senate passed the bill. The Assembly returned it to the Senate in error, but the latter again voted in favor of it. Then the Assembly refused to consider it, thereby killing it during the last week the lawmakers convened.

The local media outlets offered little explanation for the Assembly’s non-action other than reporting the lottery plan had been called “immoral and illegal” (Nevada State Journal, March 19, 1939).

The question of legality was a legitimate one, on both federal, state and public policy levels, according to then U.S. District Attorney William S. Boyle. Boyle believed tickets would have to be sold in other states for it to produce significant revenue for Nevada. Because U.S. government law forbade all interstate transportation of lottery materials and because most states at the time had their own anti-lottery laws, tickets couldn’t be sold outside of The Silver State without conflicting with those.

A second problem was within Nevada. Although the state had legalized gambling in 1931, public policy remained opposed to it, as evidenced by the courts’ refusal to hear any case involving gambling debts. Thus, no lawsuit involving a lottery payout would be allowed in The Silver State. The federal courts wouldn’t be an option either due to the above-mentioned regulations, Title 18, Sections 1301 and 1302 of the U.S. Code.

The idea of a Nevada lottery remained dead for 36 years, until lawmakers introduced two new bills in 1975 that revived the idea, which, again, didn’t pass. The state still doesn’t have a lottery today.

* Parlous = perilous, dangerous