|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1950

1950

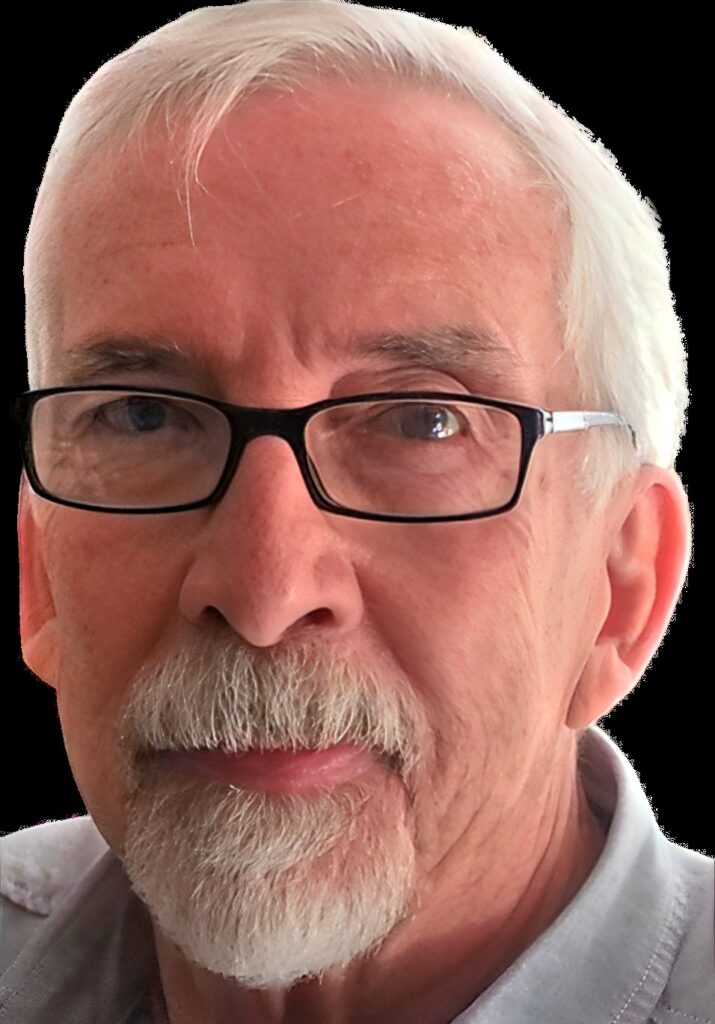

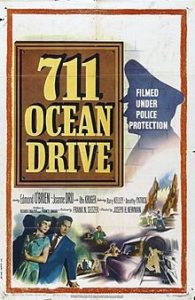

In late 1948, Hollywood movie producer, Frank N. Seltzer — known for the movies, Jungle Patrol and Let’s Live Again, which debuted that same year — began research for his next project, 711 Ocean Drive, starring Edmond O’Brien and Joanne Dru.

He intended for it to expose the “bookie racket,” or “wire service as a new industry for the hoodlums who lost out through repeal” of Prohibition,” he said (Nevada State Journal, June 15, 1950).

He planned to film in a handful of California and Nevada cities. However, Lieutenant William “Bill” Burns, with the Los Angeles Police Department, warned Seltzer he was “walking into a bear trap” in Las Vegas.

In 1949, after the script was ready, someone from the public relations firm that represented the City of Las Vegas told Seltzer they could make available famous hotel-casinos on the Strip for filming. A separate hotel owner directly offered his property for the Sin City sequences. Further, a city councilman and Chamber of Commerce member assured the producer they’d cooperate fully with production.

Obstruction, Harassment Begin

Two months later, however, when production manager, Orville Fouse, went to Las Vegas, the hotel-casino owner who had offered his property for filming asked him to his office, where there were three “bruisers leaning against the wall,” Seltzer described. The hotelier told Fouse the trio believed making the movie would be “harmful to the best interests of the city.” The PR company also reneged. Seltzer’s cameramen were denied a rental car and city airport facility services and told to return to Los Angeles where they belonged.

A false rumor that Seltzer was working on a biopic of the late mobster, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, spread around Sin City. The bogus story that Seltzer was filming for a story about mobster Mickey Cohen was perpetrated in Palm Springs.

“We are going to stop you in any way we can,” Las Vegas gamblers made clear to Seltzer.

“Frank didn’t realize what danger was in this flicker until some mobsters from Las Vegas threatened

to run him out of town — loaded with lead — when we went there on location,” O’Brien said (Lubbock Morning Avalanche, Aug. 17, 1950).

At that point, LAPD’s Burns assigned himself and four of his Gangster Squad men to escort Seltzer and the cast throughout filming.

Despite the warnings and obstructionism, Seltzer moved forward with his cinematic project as best he could. He and his production team were prevented from filming in Vegas, at Lake Mead and a well-known Los Angeles restaurant. He was nearly stopped from shooting in Palm Springs.

When attempts were made to block them from shooting scenes near Boulder Dam, Seltzer had his attorneys ask the Secretary of the Interior, Oscar L. Chapman, to intervene, which he did. Consequently, U.S. forest rangers were assigned to the crew, and filming took place but allegedly remained fraught with danger.

For instance, O’Brien, the movie’s leading man, recalled what really happened during the final sequence when his character, Eddie, was supposed to be shot with blanks by 20 riflemen during a chase through Boulder Dam, “After the take, I turned around and there were three bullet holes in a car windshield — about a foot from my head” (Lubbock Morning Avalanche, Aug. 17, 1950). “The cops cleared out all spectators including a few hoods in their midst. We had to do that scene over three more times — and, believe me, I ‘died’ each time.”

The International News Service reported, “As police know, 711 was in constant danger from hoodlums and was protected by a battery of police and plainclothesmen … 711 almost cost the lives of a few persons connected with it, including O’Brien’s.”

Seltzer presumed the gamblers’ main objection to his picture was that it revealed how past posting — faking odds and placing bets after races occurred — could beat the bookies.

Reactions Upon Movie Debut

Upon 711 Ocean Drive’s 1950 release, some critics claimed it fell short of being a hard-hitting, revelatory movie about the gambling industry. Instead, they said, it was a modest melodrama at best, “no more than an average crime picture with some colorful but vague details thrown in,” reported the Los Angeles Times (July 20, 1950).

Others lauded it for being the first to portray “the inside story of the infamous syndicate and its hoodlum empire, with its terror and violence,” and “forcefully reveal[ing] the many facets of the bookmaking business which takes millions of dollars daily from thousands of small bettors: housewives, mechanics, office workers, students,” according to Utah’s Salt Lake Tribune (July 31, 1950).