|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Frost, 1936

1906-1967

Frank “Frankie” Frost (1898-1967) spent about two decades working in Reno’s gambling scene and had close relationships with those in power locally, including gambler-Mobsters William “Bill/Curly” Graham and James “Jim/Cinch” McKay and banker and businessman, George Wingfield, Sr. Frost had a checkered past, which eventually got him blacklisted from Nevada’s gambling industry.

Here we present the “work” (criminal) highlights of Frost, tracking him geographically through Illinois, then California and, finally, Nevada.

Chicago, 1906-1930: Murder Charge by Age 30

Though Frost was born in California, he spent most of his youth in Chicago and eventually became part of its North Side Aiello–Moran gang (Giuseppe “Joe” Aiello and George “Bugs” Moran), which was involved heavily in bootlegging during the 1920s. Frost, who used the aliases Eddie Ryan, Frank Bruna and Frank Citro there, was arrested three or four times for disorderly conduct but wasn’t charged.

Also, Frost was the primary suspect in the November 16, 1928 machine gun murder of John G. Clay, head of the Laundry and Fyehouse Chauffeurs’ Union. Police theorized that Moran ordered the hit because Clay was thwarting Moran’s attempts to muscle in on the cleaning and dyeing racket in The Windy City’s West and South Sides, Alphonse “Scarface” Capone’s territory. Though Frost was arrested for the murder, he wasn’t charged.

In a supposed act of retaliation by Capone, some of his soldiers, disguised as police officers, lined up and machine gunned down six of Moran’s men on February 14, 1929, nearly wiping out his crew. Initially, Frost was thought to be among the victims of what was dubbed the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Afterward, Frost switched his allegiance to Capone.

When Chicago Tribune crime reporter, Alfred “Jake” Lingle was murdered June 9, 1930, police traced the gun, left at the scene, back to Frost but determined that a Leo V. Brothers was the shooter.

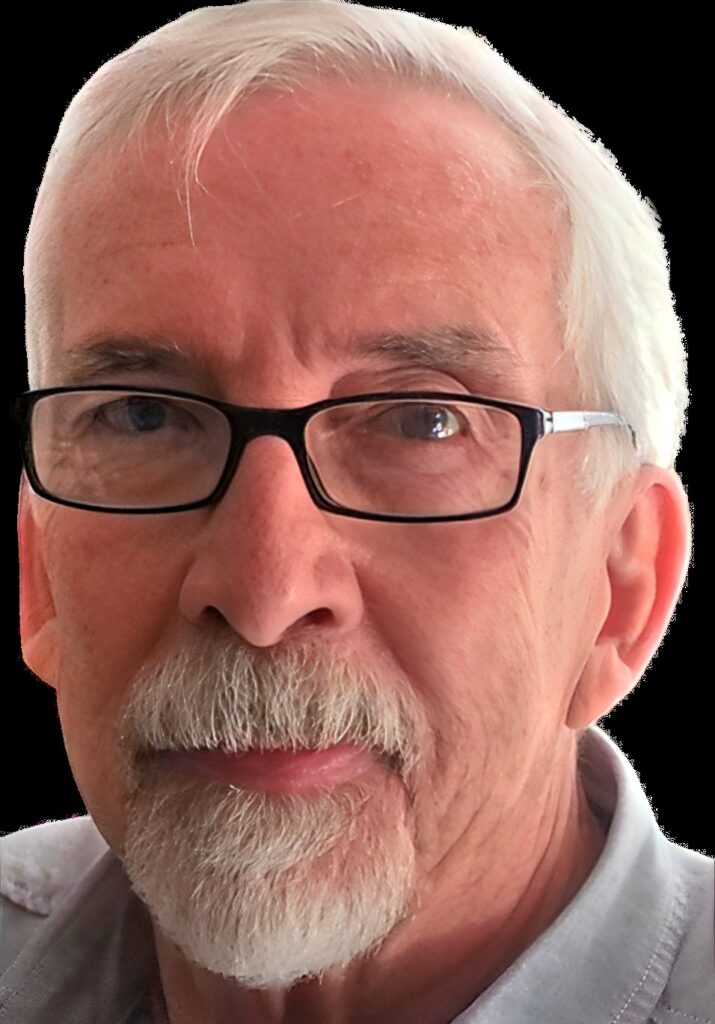

Frost

Los Angeles, 1930-1934: Not Staying Out of Trouble

Frost was indicted by a grand jury for accessory to the Lingle crime because he presumably had guilty knowledge of the killer(s) and their motives, but he was in Los Angeles at the time, using the alias Frank Foreman. He was captured there on July 1, 1930, arrested, returned to Chicago and placed in the county jail. After five months, though, he had to be released by law, so he got out on a $20,000 ($309,000 today) bond.

In March of the next year, Frost testified at Brothers’ trial. Also called to the stand was a witness who said he saw Frost and Brothers flee the scene in different directions after Lingle was shot. One detail the witness recounted was seeing Frost help Brothers light a cigarette afterward so Brothers didn’t have to take one of his hands out of his pocket.

The trial of Frost, for his alleged involvement in Lingle’s murder, was scheduled for April 28, but it never took place because the witnesses disappeared. Frost was back in Los Angeles when he learned, in June, that charges against him were dropped.

In September, Frost was arrested on suspicion of extortion in connection with a scheme to extort money from the widow of soap magnate, Leo Bergin. Bergin racked up a gambling debt of at least $6,000 ($102,000 today) in a days-long dice game run by representatives of New York gambler-Mobster Arnold Rothstein. Bergin wrote some checks for what he owed but later stopped payment on some. Before Rothstein’s men could collect in full, Bergin died, so they went after Gladys Bergin for payment. Due to lack of evidence, Frost wasn’t charged.

The following year, 1932, in February, a patrol officer pulled over Frost, who was working at the time as a bail bondsman. A search of the new car he was driving yielded a fully loaded, 0.45-caliber automatic pistol. Frost also had with him a letter from a “Ben” in New York, possibly Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, which read in part, “Other people out there are trying to keep out of trouble, but are always in touch with New York. Glad you have gone into the bonding business, as that is good cover for the business you are in.” Frost was found guilty of carrying a concealed weapon, a misdemeanor. Because he then failed to appear at a hearing of arguments concerning a possible new trial, the judge issued a warrant for his arrest.

A month later, police in San Francisco raided an apartment in their investigation of a $100,000 ($1.8 million today) jewelry robbery and took the four men inside to the station. Frost was among them. It resulted in a vagrancy charge (that later would be removed) and him being returned to the City of Angels. He was sentenced to six months in the county jail for the concealed weapon offense. Frost, though, disappeared, and a nationwide hunt for him began. Before he could be found, the appellate court reversed his conviction.

Presumably, the man who repeatedly had gotten away with crimes laid low in Southern California for the next few years.

Reno, 1935-1967: Focus on Gambling, Business

Frost next turned up living with his wife in The Biggest Little City. Only five months later, in April 1936, he was arrested for allegedly stealing $125,000 ($2.3 million today) worth of jewelry from a New York City store that January. For the story, see next blog post, Reno Mobsters Aid Gangster From Chicago, Raising Suspicions.

In 1938, the owner of a New York clothing store, Cy Kronfield Inc., sued Frost for $630.85 ($11,500 today) for not paying for goods and services it provided to him between 1933 and 1939.

Using the name Frank Foster, Frost was arrested in Elko, a city about 300 miles northeast of Reno, in May 1940 for attempted burglary of the Reinhart general merchandise store. Two months later, he was arrested and served 30 days in jail in Reno for “prowling through parked automobiles” (Reno Evening Gazette, Dec. 10, 1940). In June 1941, he was arrested for petty larceny after getting caught trying to sell children’s clothes he’d stolen from somewhere.

Frost reportedly ran or helped run the race horse pool at Graham and McKay’s Bank Club for several years, after which he opened and operated his own book, the Reno Turf Club.

In 1947’s first half, Frost applied for another gambling license from the city, this one for a new entity, Washoe Sports News, which was to supply race results from the Trans-America News and Publishing Co. wire service to local outlets. On behalf of Capone, Siegel was tasked with forcing bookmakers on the West Coast to switch to Trans-America from Continental Press. While the city council was mulling over whether or not to eliminate the existing cap on the number of race pools allowed in Reno, because granting Frost the license would’ve exceeded it, Trans-America went bankrupt and folded after its primary owner-operator was murdered. Soon afterward, Siegel was killed, too, and Frost withdrew his gambling application.

In 1951, Frost sold the Reno Turf Club. Afterward, he returned to working at the Bank Club, supposedly wrapping money. However, members of the Nevada Tax Commission, the entity which in 1947 gained the task of issuing state gambling licenses, saw him overseeing a game of faro there once. Because of his criminal background, the commissioners didn’t want Frost involved with running the gambling in any Silver State casino.

However, they spotted him again doing just that, counting money and giving orders at Reno’s Palace Club. After a related brouhaha, the casino banned him from working there in 1953, and after that, according to Frost, he no longer could get a job in the state’s gaming industry.

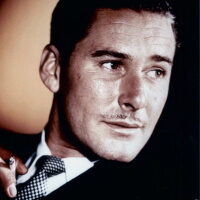

Dorothy Frost

In 1955, Frost’s wife Dorothy, a Manitoba, Canada native, took her life by overdosing on sleeping pills.

His Final Years

The widower remained in Reno and was involved subsequently in some shady business dealings, which came to light through various lawsuits. Frost held and breached the lease on the Mt. Rose Sawmill. In an incident that led to a lawsuit, Frost physically prevented a competing lumber firm (Frost owned the Nevada Pine Mill and Lumber Co.) from taking from the sawmill wood it purchased. Also, he was sued for failing to pay for lumber he bought from a Lake Tahoe man.

In another arrangement, Frost was a co-partner with McKay and Marion T. Weller in F.M.W. Drilling Co. In 1957, an employee sued F.M.W. for not paying him $1,650 ($15,000 today), the remainder of wages due him for building an oil derrick.

In 1961, a Frank Frost appeared to be working at the local Buick dealership as the assistant general sales manager. It may or may not have been him.

The Mobster Frost, who’d left a trail of crime in his wake, passed away on April 1, 1967 at age 68 in Nevada.