|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

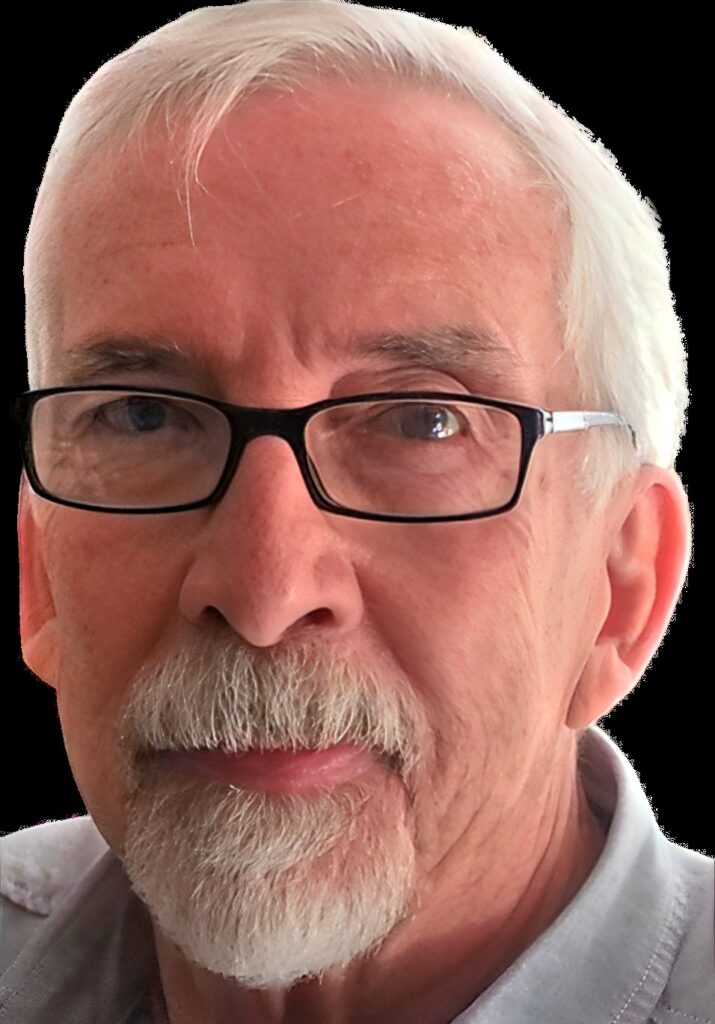

Alvin J. Paris

1946-1947

Alvin J. Paris ingratiated himself with two New York Giants football players by inviting them to parties at his apartment and taking them to nightclubs. He bet on a Giants game and gave them the payout, $500 each ($5,300 today). Then he made his move.

He promised them incentives to intentionally lose their upcoming playoff game against the Chicago Bears for the 1946 National Football League (NFL) Championship — $2,500 ($33,300 today) in cash, the winnings of a $1,000 ($13,300) wager on the Bears and a $15,000 ($200,000) job with the novelties shop Paris ran.

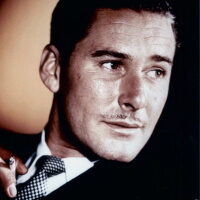

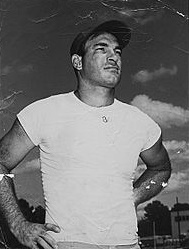

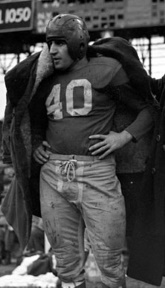

Allegedly, Frank “Frankie” J. Filchock, quarterback and halfback, refused whereas Merle Hapes, fullback, indicated he might go along with it.

Merle Hapes

The Story Gets Out

Before the Dec. 15 gridiron showdown, the NFL learned about the possible fix. The scandal went public a few hours before kickoff.

The media purported that a “big-time syndicate … said to control the betting of millions of dollars on sports events in all major cities,” was behind this scheme (United Press/Nevada State Journal, Dec. 17, 1946).

NFL Commissioner Bert Bell immediately suspended the two Giants, for a duration to be determined later. However, he allowed Filchock to play in the championship game, as the opening quarterback, reportedly because he’d denied having been approached by anyone about throwing it. The thousands of fans present booed the eight-year pro player when he was announced.

Frank Filchock

Hapes, on the other hand, admitted a gambler had tried to bribe him and, thus, was benched.

Gamblers predicted the Bears would prevail by 10 points. During play, the Giants scored two touchdowns, but Filchock’s six intercepted passes led the Bears to a 24-14 victory. As for bets placed on either team to win, the game was a push, so there weren’t any winners or losers.

In The Crosshairs

Two days later, the local grand jury returned indictments against these four allegedly involved men:

• Alvin Paris, 28, for bribery and bookmaking. Described as a playboy, Paris was the front for the New Jersey-based bookmaking enterprise of racketeer Eddie Ginsberg, his stepfather.

• Jerome Zarowitz, 32, for bribery and conspiracy. Zarowitz worked for Ginsberg as his handicapper, right hand man and sometimes bookie, and owned an estimated 20 percent interest in the business. Zarowitz had two previous arrests, for bookmaking, but no convictions. He was married, had one child and a clean U.S. Army military record. (Zarowitz, an alleged partner of the New York Genovese and Boston Patriarca Crime Families, later would become the casino manager of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas.)

• David Krakower aka Dan Kramer, Peter Krakauer, Abe Goldstein, 44, for bribery and conspiracy. Krakower, who owned a 12.5 percent interest in Ginsberg’s book operation, was a gangster who’d served time for various charges, possession of a revolver, burglary, arson, and passing and selling counterfeit Federal Reserve bank notes.

• Harvey Stemmer, 36, for bribery and conspiracy. Stemmer, also with a 12.5 percent stake in Ginsberg’s business, was a racketeer with a family and a criminal record. When indicted, he was serving prison time for attempted bribery of Brooklyn College basketball players two years earlier.

While cases against the quartet were being pursued, the NFL “sought to restore public confidence in the integrity of the ‘pro’ game,” the United Press reported (Nevada State Journal, Dec. 17, 1946).

“We are ready to take steps to combat and kill this evil thing,” Commissioner Bell said.

One Down, Three to Go

Paris, still in jail because he couldn’t raise his $28,000 ($327,000 today) bail, was the first to stand trial. There, the prosecutor introduced Paris’ full previous confession and had both Hapes and Filchock testify. Filchock admitted Paris had broached a fix with him, too.

The defense didn’t call any witnesses.

After 65 minutes of deliberating, the jurors, sequestered throughout the proceedings, found Paris guilty.

Case Against the “Conspirators”

The joint trial of Zarowitz and Stemmer, who’d pleaded innocent, and Krakower, who’d pleaded guilty, took place in March. Prosecutor George Monaghan accused the trio of “counseling and commanding” Paris in the attempted bribery of Filchock and Hapes, the Associated Press reported (Reno Evening Gazette, March 5, 1947).

As the state’s key witness, Paris testified to all of his related interactions with the defendants. (After his time on the stand, Paris received death threats.)

Patrolman Joseph Jove spoke to the contents of conversations he overheard through the 10-day wiretap on Paris’ phone leading up to the championship game. Jove’s testimony tied Stemmer, Krakower and Zarowitz to Paris’ bribing of the Giants footballers.

In his closing argument, Monaghan said, “A fine sport is now contaminated by lice and rodents. It is a good opportunity for this jury to delouse the sport and get rid of the lice that infest it” (Nevada State Journal, March 9, 1947).

The Final Fallout

The jurors found all three defendants guilty, and the judge gave them prison sentences. Krakower and Stemmer’s was five to 10 years. Zarowitz’s was up to three years. Subsequently, Paris was given a one year jail term, given his cooperation with the state.

Krakower and Stemmer appealed the ruling. However, in 1949 the Supreme Court of New York affirmed the lower court’s decision.

As for the two Giants players, Filchock’s NFL suspension was for three years, between 1947 and 1950. Hapes’ was for life, which would earn the No. 3 spot in 2015 on WhatCulture.com’s list of the “10 Most Severe NFL Suspensions Ever.”

“They barred me for telling the truth,” Hapes told the press (Nevada State Journal, April 27, 1947). “Maybe I should have lied to them. I never did a thing wrong. I just made a stupid mistake by associating with Paris Alvin, gambler.”

Which NFL teams do you predict will compete in this bizarre season’s (2020) conference championships?

———————————-