|

Listen to this blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Japanese police emblem

1974-1975

For many Japan-based businessmen, gambling trips to Caesars Palace in Las Vegas turned nightmarish.

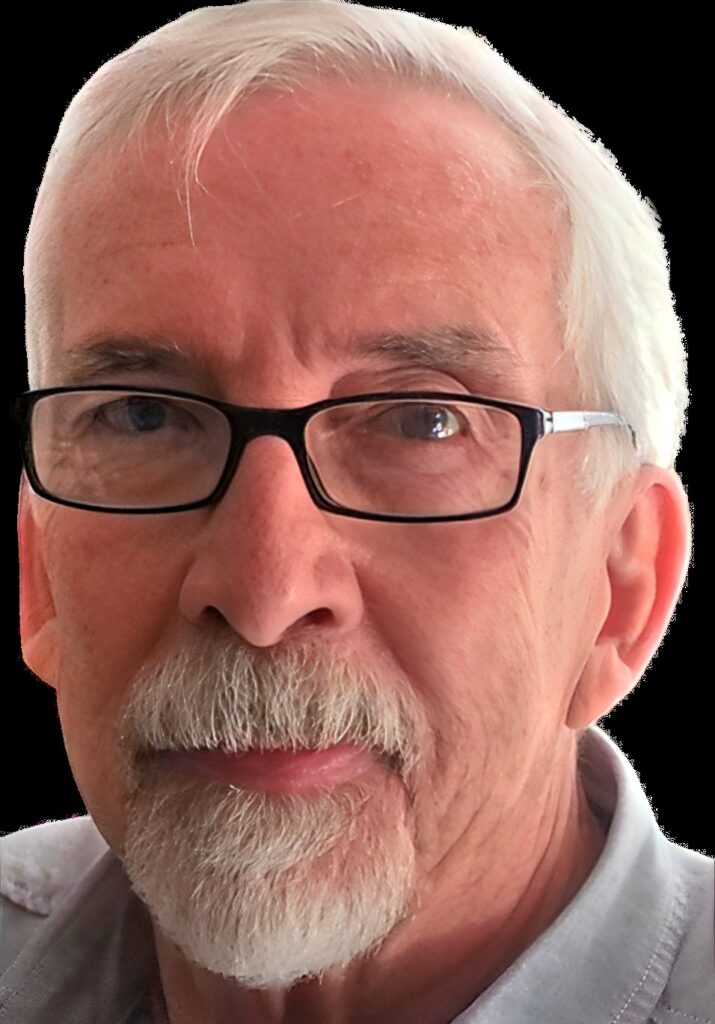

Kikumaru Okuda, 46, also a resident of the Land of the Rising Sun, and a film producer with Toho Film Company, organized numerous trips on behalf of the Nevada hotel-casino, at the request of its president, Harry Wald. Caesars Palace paid Okuda, who’d met all of Nevada’s requirements for junketeers, $3,000 ($15,000 today) a month for his services.

The agreement with junket guests, which was typical, was that the resort would pay their airfare and hotel bills in exchange for them gambling a certain number of games while in Sin City. If they won, the casino would pay them in U.S. dollars on site. If they lost, the guests would pay in yen what they owed after returning to Japan.

Illegal Collections

In the case of a 32-year-old, Yokohama dry goods dealer, upon his return home, Okuda told him he owed $93,000 (about $455,000 today) and demanded payment. (It’s likely the man hadn’t known the size of his marker or how fast it had grown when he was in Vegas.) He refused to pay.

Soon after, Okuda’s partners —Yoshihisa Kuroda, 45, and Manabu Nakajima, 40, both corporate executives — told the debtor they had Mafia and Yakuza (Japanese organized crime members) associates who’d “liquidate” him if he didn’t pay immediately (Las Vegas Sun, July 17, 1975). He gave them $18,000 (probably all he could at the time) then reported the incident to police. (Such extortion by junketeers is why the State of Nevada, in 1972, had augmented its regulations concerning junkets.)

Consequently, in 1975, members of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) investigated possible links between organized crime and gambling junkets to Las Vegas.

“In general, the situation occurred at about the same time as the movie, The Godfather, was being run in Japan, and from the point of view of the Japanese the entire affair appeared to have been engineered by organized crime interests,” wrote Jerome Skolnick in House of Cards.

Police discovered other victims, including:

• A golf course proprietor who was forced to repay $670,000 ($3.3 million today)

• A nightclub owner who had to come up with $100,000 ($490,000)

• A Tokyo jeweler who’d lost $50,000 and paid about $10,000 ($49,000)

They learned Okuda had begun the junket enterprise in January of 1974 and since then, had taken to Las Vegas 85 men, whose gambling losses had totaled $83 million ($407 million today)! Okuda had collected about $600,000 ($3 million today), two-thirds of which he’d sent to the casino through a U.S. attorney living in Japan.

The MPD arrested Okuda, Kuroda and Nakajima on charges of extorting millions of yen from Japanese citizens.

Nothing Doing

Nevada Gaming Control Board (NGCB) agents also looked into the allegation, in the United States and in Japan. When they questioned Wald, he said he was clueless as to the intimidation tactics Okuda had been using. Further, he claimed Okuda had offered to take over junket debt collection, but Okuda asserted Wald had asked him to do it. (Caesars Palace already had been in the NGCB’s crosshairs over junkets in 1969.)

When overseas, Japanese police prevented NGCB agents from reviewing any and all related documents, saying they were being held as evidence for the trio’s upcoming trial.

Back home, Nevada gambling regulators noted that opposition to and a major media campaign against gambling and junkets was growing in Japan and said the climate there toward the U.S. industry was “economically and emotionally bad” (Reno Evening Gazette, Aug. 19, 1975). Silver State officials were displeased with the circumstances surrounding the junkets from Japan and the resulting strained relations with the country.

As for Okuda, the Tokyo MPD arrested him a second-time in 1975 on different junket-related charges, but what ultimately happened to him, his henchmen and Caesars Palace — if anything — is unknown.

Art from Wikimedia Commons: by Mononomic