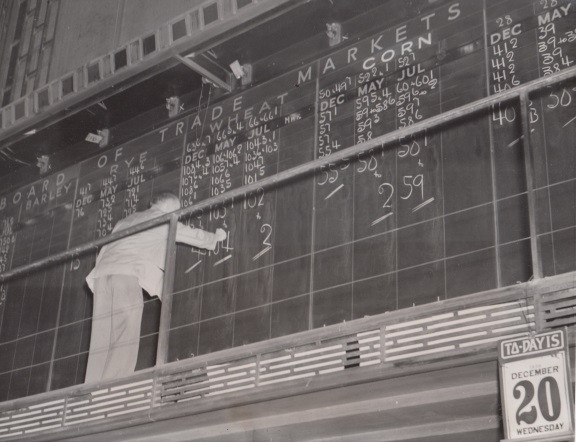

Chicago Board of Trade

1870s-1920s

“I want to go short 1,000 bushels of December wheat, 1 cent on the bushel.”

This $10 bet was typical back in the heyday of bucket shops in the United States, between 1870 and 1920. People wagered on the future prices of stocks, securities and commodities — grains, cotton, oil, etc. — without actually purchasing the goods.

“The [price] quotations are used as basis of this species of betting as a gambler uses dice to decide the bet [in games like craps],” wrote John Hill in Gold Bricks of Speculation.

How It Worked

In the bucket shop, prices for various commodities were listed and updated on a blackboard as they changed according to the Chicago Board of Trade or whatever exchange was used. The shops often obtained the price quotes via telegraph.

The customer bet the shop that on a certain day or in a given month in the future a commodity would be worth a specific amount. If, at that time, it was, the wagerer won minus the shop’s commission. If it wasn’t, the shop profited. Because of the commission, which the customer paid whether they won or lost, however, the disparity between the amounts the customer and the shop made on a bet was significant, clearly favoring the house.

Say in the example above, the price of wheat was $1 a bushel, and the customer bet it would drop 3/4 of a cent. If it did, he made $5 — 3/4 of a cent minus 1/4 of a cent commission (equaling 1/2 cent), times 1,000 bushels.

But if it went up that much, the bettor lost and the house made $10 — 3/4 of a cent plus 1/4 of a cent for commission (equaling 1 cent), times 1,000 bushels.

“These ‘bucket shops’ flourish for the most part upon the patronage of men and women of small means who imbued with the get rich quick idea, venture or risk that which they can ill afford to and which, once being deprived of, entails hardship and privation upon themselves and their families,” noted the San Francisco Call (Jan. 4, 1911).

Bucket shoppers, or owners of these gambling businesses, often cheated by fabricating the exchange’s price quotes to their advantage to garner profits because patrons couldn’t or wouldn’t try to verify them. Some capitalized on their clients’ naiveté, encouraging them to repeatedly add money to their original stake. Others welshed on paying out winnings.

One such San Francisco, California bucket shopper who found himself frequently in the news was Henry A. Moss.

Eradication Efforts

In the late 1800s/early 1900s, numerous city and state governments banned bucket shops, including those of Chicago, Los Angeles, Missouri, New York and North Carolina. San Francisco outlawed them in 1911. In 1909, the U.S. Congress passed amendments — an Act to Prohibit Bucketing and Bucket Shopping and to Abolish Bucket Shops — to the 1901 Act to Establish a Code of Law for the District of Washington, D.C.

The federal statute “was enacted as a part of President William Taft’s war on the meanest of all the sure thing gambling systems,” reported the San Francisco Call (March 18, 1911).

Not only were bucket shops considered to be a gambling evil, but they also were blamed for contributing to the 1870s agricultural depression and the 1901 and 1907 U.S. stock market crashes because they created “a powerful concentrated interest for the depression of values,” (San Francisco Call, Feb. 4, 1892).

Photo from Acme Newspapers